The Eve Of... Public Forum

A public forum to accompany The Eve of... was held in the gallery on September 24, 2014. It featured guest dialogist Andria Hickey, Public Art Fund Associate Curator. What follows is a condensed, edited transcript of the conversation, which spanned emotions in sculpture, works in the show, artistic development, artist-run culture, and the livability of New York for artists.

Andria Hickey: A Promise is a Cloud, the Public Art Fund show that I curated a few years ago at Metrotech, was a group of sculptures that all referenced the body. All of the artists talked about their own physical relationship to the object they were making, as if there were an aura around the object. That’s not new, but I think things like research-based practice bring it to a different level. A lot of artists are pulling in different kinds of bodies of research, but then have this completely mute object that really is about feeling. They’ll actually tell me like, ‘This is a whale bone from a ship that was rescued by so-and-s0,’ … but then the actual object has a metaphysical relationship to the viewer.

Ohad Meromi, Stepanova, 2011. Exhibition view in A Promise is a Cloud, Public Art Fund. // Photo: James Ewing. Courtesy Ohad Meromi and Harris Lieberman Gallery. // Source: publicartfund.org.

Christine Wong Yap: I think it’s so interesting how a thing can accrue meaning, and to think about where that meaning lives, whether it’s in the object or in the person, and if it only exists between those two—like if somebody else finds it at a garage sale, if it also has that power or not.

AH: …Why shift towards the dark side?

CWY: Partly because I think, with my past work, people didn’t realize I did a ton of research into emotions, and some people interpreted my past projects as being cynical. And partly because I was looking at my work having to do with optimism and pessimism and wanted to make work that’s more formal or phenomenological, and less about conveying research or ideas.

AH: How did you decide on the materials for these kinds of works?

CWY: I did a project called MegaPennant and MegaPentimento. It was a series of pennants made of transparent vinyl. By layering them, they became opaque and dark, and the shadow became heavy. It was trying to convey that happiness is not just one single emotion of joy or cheerfulness, but it’s actually many more things like purpose and meaning that take a lot more work. The thing about the material is this: more colors doesn’t mean more colorful. I was thinking about density and feeling, shadows and mystery.

MegaPennant and MegaPentimento, 2012, vinyl, twill tape, aluminum, wood, 96 x 72 x 1 inches / 2.4 m x 1.8 m x 1 cm and 96 x 72 x 10 inches / 2.4 m x 1.8 m x 25 cm. Supported by Lucas Artists Program at the Montalvo Arts Center.

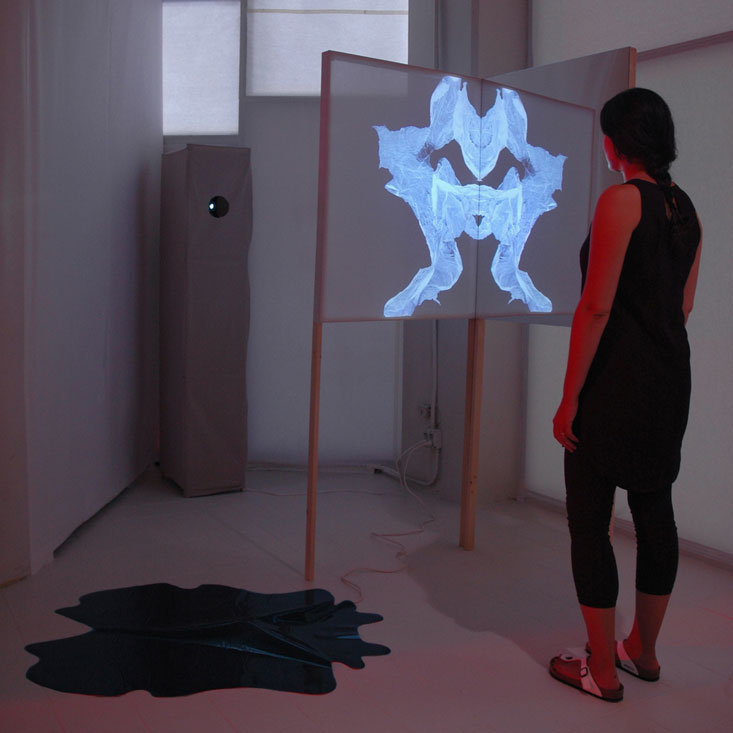

AH: This isn’t the first time that you’ve implicated the viewer in the machinery of the artwork. Like in the installation, Doorway. You’re showing me earlier, how your body interrupts the light in an interesting way [casting a shadow in which a smaller, displaced halo and shadow can be seen].

Doorway (interaction view detail), 2014, wood, vinyl, asphalt-based coating, lights, stands, gels, door: 82.5 x 33.5 x 5.5 inches / 210 x 85 x 14 cm

CWY: I was thinking about embodiment; how certain emotions, when they’re really intense, are also felt in your physical being. So I wanted to bring forward psychological and physical experiences by making things at a body-like scale, or having the viewer become part of the work.

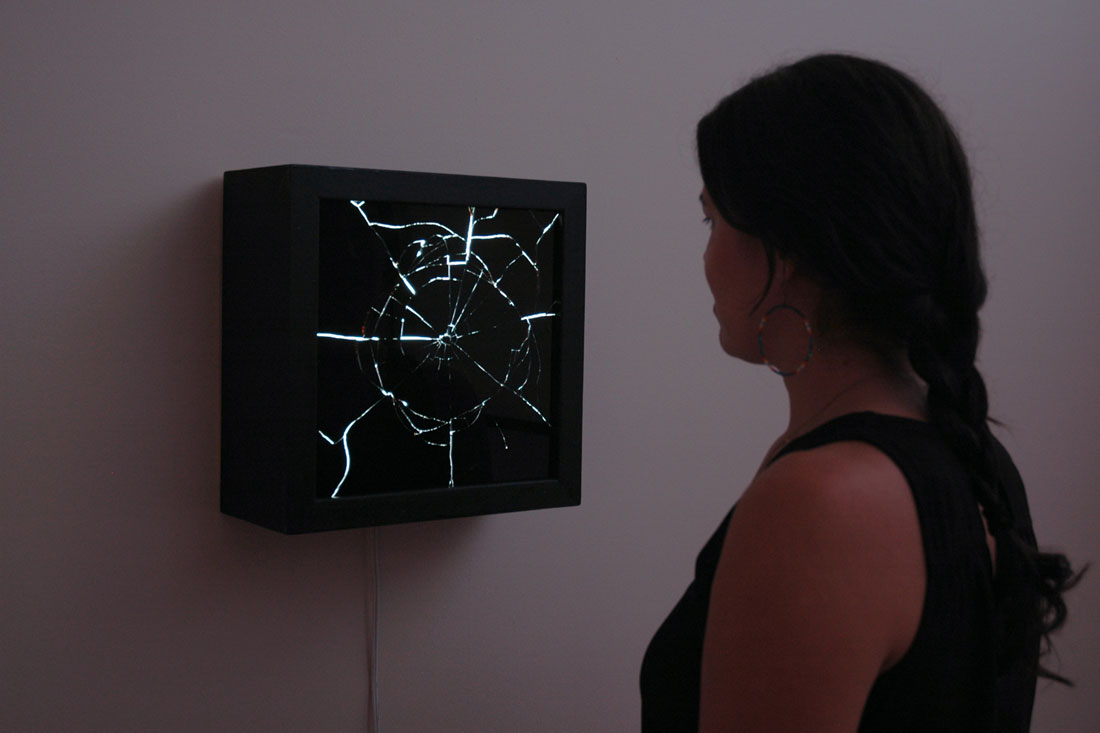

Hank Willis Thomas: Most of the shapes are unrecognizable. I was interested in how there are more abstract works [Mirrors] and then more formal ones [like Mummy Bag]?

Mirror #1, 2014, wood, asphalt-based coating, light, acrylic, mirror, 13.625 x 13.625 x 5.5 inches / 34.6 x 34.6 x 14 cm

Mummy Bag, 2014, vinyl, thread, discarded clothing, 5 x 80 x 29 inches / 13 x 203 x 74 cm

CWY: It wasn’t a conscious decision. When I started this show I had a bunch of gut feelings I wanted to follow. Knowing that I was doing this pop-up gallery and running it myself freed me to just try stuff. So Mummy Bag was one of the things.

HWT: Does Mummy Bag fit anyone?

CWY: It’s based on a pattern I took off of a real mummy bag—

AH: Like a mummy sleeping bag.

CWY: Yes.

AH: I thought ‘body bag’ when I saw it. … It’s a really big departure. … You also mentioned going through a process of thinking about trauma and that shift between organization and disorganization—that un-doing space…. The field of trauma theory is very intense, interdisciplinary and complicated. It’s a body of research that came out of the Holocaust, mostly. Susan Sontag’s theories of images are based on trauma theory and psychoanalysis related to trauma. But it comes out of a mixed field of cultural studies, psychology, being subjective witness versus secondary witness, etc. I wonder if you did any research into trauma theory?

CWY: No. I heard of this idea of post-traumatic growth. Positive psychologist Martin Seligman researched how traumatic events can lead not just to post-traumatic stress but also post-traumatic growth. But I wanted to situate this work in the place after the setback and before the decisive action; before language, thought, and action. That pause.

HWT: So, this feels like a transition? When I hear you say post-traumatic growth, it seems more like your prior work…. Is your future work going to incorporate a phase of action, then?

AH: That’s a good question! What comes after this?

HWT: This could be a new step into a new area, as you’ve been working with these prior themes for at least four or five years, right? So you can go deep into the dismantled self.

CWY: In Doorway, there’s a front and a back, and a past and a future, but you can’t tell which is which. They’re mixed up. So I am not seeing this as part of a linear progression.

Doorway (interaction view)

AH: I think it’s interesting that whenever I thought about your prior work, it almost had a social justice element. You know, to me, the world we live in sucks, and your work felt like a positive action. So it had a greater relationship to the general world versus an internal, emotional process. This feels more internal, and it’s situated inside, whereas past pieces have outside or public dimensions.

CWY: I hadn’t thought about that. I still think about the viewer participating in the work. And yeah, it does come from a personal place.

AH: I mean the viewer is implicated, such as in the light in Doorway. It’s an internal experience—

CWY: It’s introspective.

AH: Yeah, the other work is about joining others, connecting together.

HWT: …an activist element, of calling to action… With Projection, you’re aware of your reflection and your positioning, which I think affects me like, ‘How am I seeing myself?’ Mirror #2 feels the most like a departure, you’re looking into something, and there’s refraction, and the fact that you have a mirror surface but because it’s backlit it becomes not a mirror.

Installation view of Hide and Projection

Mirror #2, 2014, wood, asphalt-based coating, light, acrylic, Mylar, window tint, 13.625 x 13.625 x 5.5 inches / 34.6 x 34.6 x 14 cm

AH: I have a question for everybody. Have you ever done this kind of self-initiated residency? I think that’s really exciting.

David Wilson: I go to a cabin. Actually the first thing that I thought about when I walked in here was that it sort of feels like a landscape…

AH: You’re also free from institutional bureaucracy…. With public art, there’s a lot of work you have to do. This is very different. It’s almost anarchic in its separation from things.

DW: ...People don’t experiment…. it seems like the best thing that a forward-thinking, critical project can get you to, is a place where you’re experimenting….

HWT: It’s hard to experiment in the context of NYC—

AH: It’s impossible—

HWT: I think New York is a very hard place to be creative. Not that you can’t make art. But being creative—actually forcing yourself out of your box, out of your own way of thinking—a lot of people in New York find it challenging. …in your activist, anarchic way, it kind of works, and situates an opportunity for other people to make work in that way.

AH: You have a thing you say: Make—

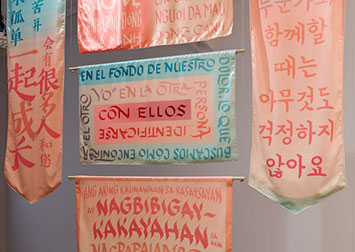

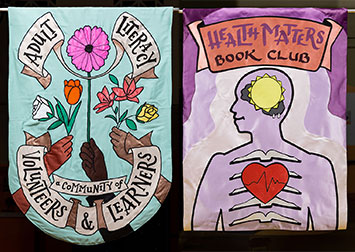

CWY: Make things happen. It’s part of a show that Hank curated. It’s on now.

HWT: At Nathan Cummings Foundation, and will be at New York University.

CWY: Tattfoo Tan does similar projects, enabling people to do stuff outside of institutions, such as a re-granting grant.

Tattfoo Tan: For me, a lot of projects don’t have to be masterpieces. I’m just trying something out. I took the idea from startup companies… I do smaller projects, and hopefully produce bigger ones. If not, then I drop them… I don’t know where all of this goes. It’s just one step at a time.

AH: I think New York could use artist-run culture. In Canada it should end. It has almost no commercial art world and it really affects art making, because the artist-run culture is thirty years old. But at the time when it started, there was nothing. Artists organizing around each other could really happen here. … It seems like something needs to change in this city. It seems like something needs to happen, and I don’t know that alternative spaces are actually alternative at all. They’re just smaller bureaucracies that are just horrible to work in, and difficult for artists. The idea of saying, ‘No, we’re not going to be part of something else,’ is a good idea. … So maybe, Christine, you just have to start your own artist-run center.

CWY: But wouldn’t that become another institution that would become ossified?

AH: No, the whole idea of artist-run history, is that it was a space like this and a phone. It was just artist-organized, like a real start-up. … What happened in Canada—they became so bureaucratic, but it took thirty years, so there were a few years that were amazing and different things happened. And that’s more important.

CWY: … I was thinking about artist-collective galleries Regina Rex and Ortega y Gasset, but they’re being squeezed out… There’s so many factors outside of artists’ control…

DW: I hear these kinds of things everyday… People who’ve lost their lofts…

AH: The whole city feels like it’s unattainable for artists… I think in the next ten years in NY it will not be possible for artists to rent space, unless they are a certain level in their career. It will be remain only a commercial art world center.

Michael Yap: [The works on view] are all so different. Was there an intention to make them different?

CWY: Yes. Public Art Fund puts on a really great lecture series at New School, and I really liked Iran do Espírito Santo’s. He does these phenomenological installations. One of the things he said was that he thinks of how viewers walk through the space “cinematographically.” I really appreciated that phrase and thinking about space as well as time. I was thinking of the space as a space with many spaces within it, something with a durational aspect.

Iran do Espírito Santo, Switch, 2012, latex paint on wall, dimensions variable. // Source: skny.com.

AH: I think what’s happening here is still an exhibition; it’s not an installation. Have you ever thought about pushing the practice more towards installation? Doorway could be its own installation.

CWY: Actually, when I was first sketching, I was thinking about doing one big installation. And that became Doorway.

AH: And Projection could be an installation too.

CWY: This is the other thing—I get to play exhibition design and curator and art handler of my own work. I enjoy that.

AH: It’s a lot of labor. But the freedom of not having other voices in the room can be really liberating.

The Eve Of... is supported by an Individual Artists grant from the Queens Council on the Arts with public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council. Support from the Falchi Building and Whole Foods is also gratefully acknowledged.

Special thanks to Andria, Hank, David, Tattfoo, and Michael.

_Partner=Unfinished_Photographer=JeffScroggins_Ig@jscrogginsphoto_002-355x252.jpg)